Recognition, strikes and pickets: welcome to a forgotten language

The staff at Times Radio gave me some funny looks this week, well, more than usual. We were talking about Labour’s plans to give power back to unions and I started rabbiting on about how recognition works and how it was the stepping stone to collective bargaining and even sector pay deals. I might as well have been speaking a lost language.

Which I was. Trade unions have been stripped of their economic power in the past five decades and with it their place in the public consciousness and language. When I started work nearly 40 years ago, one of the first things new recruits did was to join the union. Now it would not cross most people’s minds.

Union power was a real thing. A reporter who joined at the same time as me came back to her desk one afternoon ashen-faced after receiving a furious telling-off from a gaggle of senior executives. Her crime? She had been in the composing room, one floor below the newsroom, and carelessly had picked up a scalpel left lying on a paste-up desk. This was breaking a taboo. Only compositors, represented by a different union, could touch their tools. Journalists could not and there was the real prospect of a lightning stoppage that would have killed a couple of editions of that day’s paper. It all blew over, but, bizarre as that sounds today, it was not out of the ordinary. Demarcation was demarcation and you knew not to mess about.

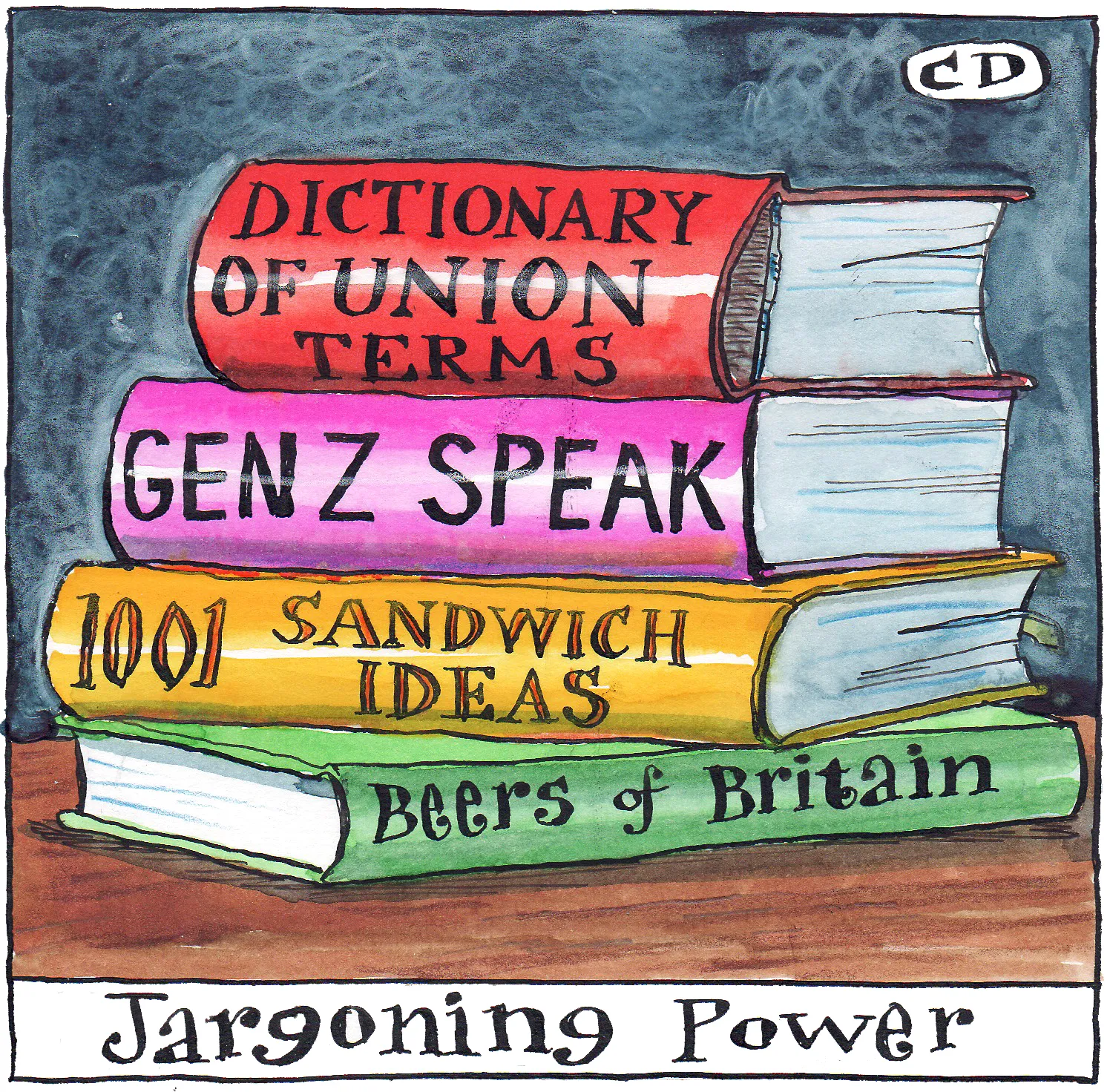

All this poses something of a problem for Labour supporters wanting to burnish their progressive credentials and be up to speed on the plans to boost union power. They might be able to name all the genders and recite the elements of inclusive education, but do they know their closed shops from their flying pickets? It’s also an issue for those who oppose the plans. You can’t argue effectively if you don’t know the terms. Here, then, is a helpful guide to all the jargon of a bygone age.

Recognition first. An employer can “recognise” a union to represent staff, or a group of staff, and to negotiate pay and other terms and conditions on their behalf. If everyone is covered, that is collective bargaining. It used to be the norm, but the Office for National Statistics’ Labour Force Survey suggests that only a quarter of workers are now covered by a collective agreement. That is probably a big overestimate. The number was arrived at by asking workers how their pay was determined, not by counting the number of agreements.

Recognition can be voluntary. The union asks and the employer says yes. If it’s a no, the union can force the employer into “statutory” recognition. The 2016 law, which Labour says it will repeal, puts several hurdles in the union’s way. First, it has to have 10 per cent membership. Then it has to prove that more than half the staff want it to come in, which normally means a petition or a ballot. The evidence has to be presented to the Orwellian-sounding central arbitration committee, which will decide whether the employer has to play ball or not.

Recognition is a union’s lifeblood. It means a guaranteed source of members, more income and more power. Some of the big, although usually hidden, industrial relations battles in the past were not union versus employer but union on union. If you could muscle into a big industry and push out the existing union, that was a coup. This was often done with the connivance of the employers, who would hope that the new union would be more docile than the old, and they might even have done a backroom deal to ensure it.

Recognition is also the gateway to all the other fun stuff, like the forbidden scalpel. If there is more than one recognised union, there could be strict limits on what the members of each union could do. This was demarcation and it was often taken to farcical lengths. Strong unions might eventually force an employer to offer work only to their members — no union card, no job. This is the closed shop, once common but made illegal in the UK in 1990. Illegal, but perhaps not completely gone. In 2015 Sajid Javid, the business secretary at that time, announced an inquiry into what he regarded as de facto closed shops in some public services.

Strikes were also once extremely common. Electricity workers and miners struck so often in the 1970s that the Heath government brought in a three-day working week to save power. If you look at the ONS chart of working days lost to strike action each month, things were particularly fractious in September 1979, when 11.7 million days were lost, nearly double any other month since 1931, when records began. The number slid into the tens of thousands for the three decades after the 1990s but has perked up recently, thanks to action by rail staff and doctors.

Strikes can be official or unofficial. Official strikes follow rules. There must be an independently scrutinised ballot of members and 14 days’ notice before strike starts. If you take part in an official strike, you are, in theory at least, protected from any retaliation by the employer, such as being sacked or suffering discriminatory treatment in the future. There might be a picket — a demonstration by workers — and if you cross the picket line and go to work, you will be called a scab.

Unofficial strikes don’t follow rules and don’t afford any legal protection. Some of the most effective industrial action has been unofficial. The big change in pay, terms and safety for North Sea workers after the Piper Alpha disaster, for example, came from action orchestrated by the Offshore Industry Liaison Committee, not an official union. Unofficial action makes employers uneasy, and unions, too, because it indicates that they have lost control of the membership.

If you go on strike in support of workers in another industry, you are taking secondary action, which is unofficial. If you take your picket line to another workplace, you have become a flying picket and probably have laid yourself open to a claim under civil law.

One final wrinkle on strikes. Employers can take industrial action, too, and can prevent workers from entering the premises. This is a lockout and usually it is used only when things have got really bad and the employer is trying to force an agreement on its terms.

That little trip down memory lane should leave you equipped to hold your own when the debates start about Labour’s plans. If you think it’s not needed, have a read of the party’s 2021 green paper, the blueprint for what is about to come. It promises, among other things, easier recognition, a big increase in collective bargaining, sector-wide pay deals and less strict rules around strike ballots. The economic pendulum that has swung away from labour towards capital for the past 50 years is beginning to swing back. The question now for Sir Keir Starmer’s new government is how far it wants to let it go.

Dominic O’Connell is business presenter for Times Radio

Post Comment